Dressage is living a paradox. Every year, foals are born with increasingly refined genetics, spectacular movement, and access to breeding and training programs never seen before. And yet, the percentage of horses that actually reach Grand Prix remains minimal. What happens along the way? Is it truly that difficult to reach the top, or are we asking too much?

The Road to Grand Prix: An Endurance Race

A Grand Prix horse usually requires between 8 to 10 years of constant training. This means keeping the same horse:

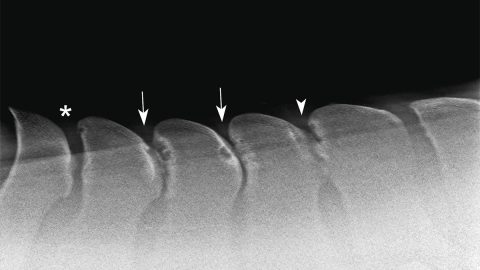

- physically sound, avoiding injuries to joints and the back,

- mentally strong, able to withstand pressure and complexity,

- and emotionally motivated, something that only happens when training is based on trust and logical progression.

The demand is enormous: in a single test, the horse must show everything from maximum collection to full extension, shifting in seconds from piaffe to passage, from pirouettes to one-tempi changes, with barely a breath in between.

Is the Test Too Long?

The Grand Prix test lasts between 6 and 7 minutes, in which the horse executes over 30 scoring movements. The intensity is extreme, and the concentration required borders on the superhuman. Many horses, even with talent, lose quality towards the end: cadence fades, neck tension increases, straightness is compromised.

Should we not ask ourselves whether the length and density of the test are excessive?

Other equestrian disciplines have already adapted their formats to improve the spectator experience while reducing the physical toll on the horses. Why not dressage?

The Bottleneck: From Small Tour to Grand Prix

The most difficult leap in a horse’s career is the transition from Small Tour to Grand Prix.

- Piaffe and passage demand a strength in the back and in the mind that not every horse can achieve.

- Pirouettes, one-tempis, and the seamless flow between all these exercises act as a natural filter, leaving many combinations behind.

An often-overlooked factor: not every horse is bred for mental resilience. Modern breeding tends to prioritize expressive movement, elasticity, and brilliance — but sometimes sacrifices the toughness and repeatability needed to endure 10 years of training and arrive fresh at Grand Prix.

The Role of Breeding

As both a breeder and a rider, I see a clear trend: we are producing stunning horses with impressive gaits, but not always with the physical and psychological durability for the demands of top sport.

The question we should ask is: are we breeding horses for real sport or for the auction arena?

The great Grand Prix horses we all remember — from Rembrandt to Totilas, from Valegro to Dalera — did not just have quality. They had endurance, mental stability, and work ethic. Qualities that often cannot be spotted in a video of a 3-year-old.

The Pressure of the Competition System

Another factor is the pressure from the competition structure.

- Horses are presented too young at international shows, often asked to demonstrate movements for which they are not yet ready.

- The market demands quick results, which compromises the logical progression of training.

- Riders, under pressure from owners and sponsors, sometimes rush stages that should be consolidated with patience.

The outcome: brilliant horses at 6–7 years old that fail to establish a lasting career at Grand Prix.

Does Dressage Need Structural Reform?

Perhaps the key lies in opening a deeper debate:

- Should we review the length and density of the Grand Prix test?

- Is it realistic to ask for the entire repertoire of advanced dressage in just 7 minutes?

- Should we introduce intermediate tests between Small Tour and Grand Prix to ease the transition?

Dressage is tradition, but it is also an Olympic sport. And if it wants to stay alive, it must evolve — both to preserve the welfare of the horse and to attract new riders and new spectators.

Conclusion

Reaching Grand Prix will always be difficult — and perhaps it should be, as it represents the pinnacle of the sport. But if we want to see more horses at this level, we must question the fundamentals:

- breeding,

- training systems,

- the competition calendar,

- and the design of the test itself.

A more sustainable Grand Prix would not only mean more horses at the top, but also happier, healthier, longer-lasting athletes — capable of moving the audience for many more years.